Die Grundlage des geltenden Sprachenkonzepts mit zwei Fremdsprachen auf der Primarstufe bildet die EDK-Sprachenstrategie aus dem Jahr 2004. Diese wurde mit folgenden Argumenten untermauert: “Frühes Lernen ist aus neuropsychologischen Gründen namentlich für den Erwerb von Sprachen besonders wichtig und profitabel: frühes Sprachenlernen ist effizienter, schafft günstige Voraussetzungen für das Erlernen weiterer Sprachen und fördert das Entwickeln von Strategien für das Sprachenlernen.”[1] Die Annahme der Überlegenheit des frühen schulischen Fremdsprachenlernens basiert auf einer Vermischung von natürlichem Spracherwerb mit sehr hoher Kontaktzeit und dem schulischen Fremdsprachenlernen mit nur wenigen Lektionen pro Woche. Diese beiden Lernkontexte sind nicht vergleichbar und Erkenntnisse des natürlichen Spracherwerbs dürfen deshalb nicht als Rechtfertigung für den frühen schulischen Fremdsprachenunterricht verwendet werden. Ausserdem halten die neuropsychologische Argumentation und deren Hypothesen für die Schule einer genaueren Prüfung nicht Stand.

Tabuisierung mit wenigen Ausnahmen

Nachdem eine Vielzahl von Studien seit den 1970er-Jahren aufgezeigt hat, dass ältere Lernende im speziellen Kontext des schulischen Lernens dank ihren besser entwickelten kognitiven Fähigkeiten bevorteilt sind, hat sich die Wissenschaft in der Zwischenzeit anderen Fragen zugewandt. Das Thema des optimalen Startzeitpunkts des Fremdsprachenunterrichts ist gleich im doppelten Sinne abgehakt: Erstens herrscht grosse Einigkeit darüber, dass schulisches Fremdsprachenlernen mit ein paar wenigen Lektionen pro Woche für junge Lernende keinen Vorteil ergibt. Zweitens weigert sich die Politik – im Verbund mit den Medien – bisher standhaft, trotz den ernüchternden Ergebnissen auf ihren Beschluss zurückzukommen.

Allerdings gibt es in der Schweiz bemerkenswerte Ausnahmen:

- Beispiel Kanton Appenzell Innerrhoden: Nur eine Fremdsprache (Englisch) an der Primarschule. Französisch wird erst ab der Sekundarschule erteilt. Die Appenzeller besuchen die beruflichen Gewerbeschulen und andere weiterführende Schulen im Kanton St. Gallen. Trotz des späteren Beginns mit Französisch gibt es keine zu beobachtenden Unterschiede zwischen den Schülerinnen und Schülern aus Appenzell und St. Gallen.

- Beispiel Kanton Uri: In der Primarschule ist mit Englisch nur eine Fremdsprache obligatorisch. Die Schülerinnen und Schüler haben ab der 5. Primarklasse die Wahl zwischen zwei Lektionen Italienisch oder je einer zusätzlichen Lektion Mathematik und Deutsch. An der Oberstufe kommt neu Französisch als obligatorisches Fach dazu.

Die folgenden Abkürzungen sind für das Verstehen der Quellen erforderlich:

AoO = age of onset = Alter zu Beginn des Fremdsprachenunterrichts

ECLs = early classroom learners = früher mit dem Fremdsprachenunterricht beginnende Lernende

FL = foreign language = Fremdsprache

LCLs = late classroom learners = später mit dem Fremdsprachenunterricht beginnende Lernende

1.

Berthele, R. (2019). Policy recommendations for language learning: Linguists’ contributions between scholarly debates and pseudoscience

Journal of the European Second Language Association, 3 (1), p. 1-11. [2]

“… there is agreement that an earlier start of FL teaching does not consistently lead to better proficiency”. (p. 6)

“… Instead of critically reviewing the research on the effects of AoO in FL teaching, many scholar-advocates enriched their publications by irrelevant references to brain research”. (p. 6)

“… it is a general feature of the programmatic literature on (early) FL learning that it is mainly informed by the introspection of language experts and by surrogate research outcomes from badly fitting samples of multilinguals”. (p. 7)

“… the studies that are available of AoO and FL learning are far from clearly supporting the earlier onset in the sense of the converging evidence”. (p. 7)

“… If early French FL instruction does not produce the expected results, it is our duty to report this and to question the assumptions that lead to the policy recommendation”. (p. 9)

2.

Schlussbericht zum Projekt «Ergebnisbezogene Evaluation des Französischunterrichts in der

6. Klasse (HarmoS 8) in den sechs Passepartout- Kantonen»

Durchgeführt von Juni 2015 bis März 2019 am Institut für Mehrsprachigkeit der Universität und der Pädagogischen Hochschule Freiburg im Auftrag der Passepartout-Kantone (2019). [3]

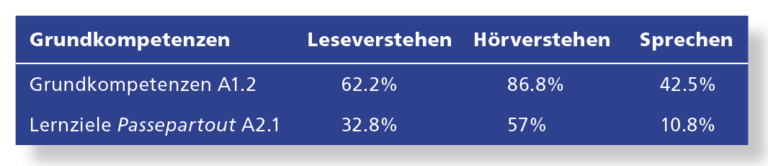

“Während die Ergebnisse im Hörverstehen tendenziell positiv gewertet werden können, weisen die Resultate im Leseverstehen und besonders im Sprechen auf weiteren Entwicklungs- und Handlungsbedarf hin, denn ein beachtlicher Teil der Schüler/-innen erreicht am Ende der Primarstufe auch ein elementares Niveau (A1.2) bei den Sprachkompetenzen nicht”. (Abb. 2)

Abb. 1: Erreichung der Grundkompetenzen (A1.2) und der Passepartout-Lernziele (A2.1) nach

Fertigkeiten (Institut für Mehrsprachigkeit der Universität Fribourg)

3.

Pfenninger, S. E., and Singleton, D. (2017). Beyond Age Effects in Instructional L2 Learning: Revisiting the Age Factor. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Die Studie ist die bisher einzige Schweizer Langzeitstudie, welche frühe mit späten Englisch-Startern und -Starterinnen vergleicht. Die Datenerhebungen erfolgten zwischen 2009 und 2015.

“There is no evidence that an early start in FL learning leads to higher proficiency levels at the end of mandatory school time”. (p. 56)

“… despite their markedly fewer hours of instruction, the LCLs did not seem to suffer from weaker lexical access and poorer lexical knowledge… The LCLs even had significantly higher accuracy scores in the detection of regular past violations.” (p. 68)

“To be noted, however, is that subsequently, in the long run, none of the tested skills turned out to be negatively affected by a later AoO”. (p. 81)

“… the efforts to effect a successful introduction to the FL at primary school seem not to bear fruit later in secondary school.” (p. 82)

“… the LCLs were also less anxious than the ECLs … and they had more positive attitudes towards FLs and the learning situation. … the ECLs had extremely unfavourable attitudes towards FLs in general.” (p. 110)

“… the decrease in early enthusiasm to learn an FL over a longer period of instruction has been frequently observed.” (p. 113)

“Our results thus run counter to the commonly held view that younger school learners have a more positive attitude towards an FL than older school learners …”. (p. 135)

“Just six months into secondary school, the five-year difference in instruction time had no significant effect on the learning outcome with respect to the English article system”. (p. 167)

“Given the increasing number of early FL programmes in Europe, and their consistently very disappointing outcomes, state schools should perhaps consider offering more immersion programmes or exchange programmes at secondary level.” (p. 210)

“The central belief around which this myth (earlier is better) is woven assumes that formal learning of a second language (L2) at an early age is inevitably more likely to lead to the successful acquisition of that language. Real empirical evidence of long-term advantages emerging under such conditions is in fact not available.” (p. 211)

4.

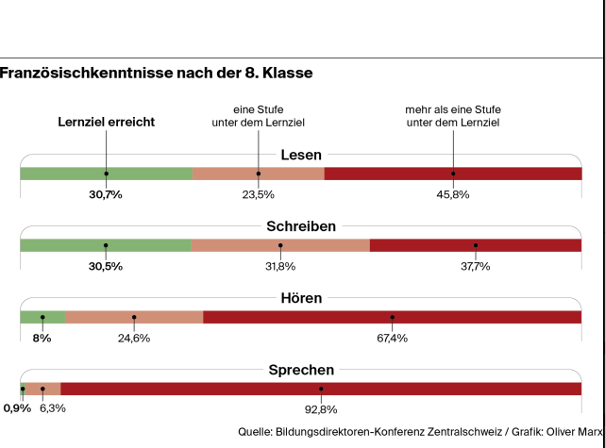

Elisabeth Peyer, Mirjam Andexlinger, Karolina Kofler, Peter Lenz (2016). Projekt Fremdsprachenevaluation BKZ, Schlussbericht zu den Sprachkompetenztests.

Durchgeführt vom 1. Oktober 2014 bis 7. Dezember 2015 am Institut für Mehrsprachigkeit der Universität und der Pädagogischen Hochschule Freiburg im Auftrag der Bildungsdirektoren-Konferenz Zentralschweiz. [4] (Abb. 2)

Abb. 2: Französischkenntnisse nach der 8. Klasse

(Institut für Mehrsprachigkeit

der Universität Fribourg)

5.

“Im schulischen Kontext zeigt sich derselbe Startvorteil für ältere Lernende. Sie lernen schneller als die jüngeren. Ein Ein- und Überholen durch die Frühbeginner wird in den momentan verfügbaren Studien im Allgemeinen nicht nachgewiesen.” (S. 58)

6.

Mihaljevic Djigunovic, J. (2009). Impact of Learning Conditions on Young FL Learners’ Motivation.

In: Early Learning of Modern Foreign Languages (Ed. by Nikolov, M.).

«Comparative studies might offer information on the minimum required conditions beyond which early learning of foreign languages not only does not benefit young learners but may be detrimental to successful further language learning as well as their affective learner characteristics.» (p. 88)

7.

Nikolov, M. (2009). Early Modern Foreign Language Programmes and Outcomes: Factors Contributing to Hungarian Learners’ Proficiency.

(Ed. by Nikolov, M.).

“Correlations show weak relationships between years of language study and students’ performances in years 6 and 10 in both languages and across the three skills. As a devoted advocate of an early start, stronger relationships would have been expected.” (p. 98)“

“These findings seem to challenge the efficiency of early programmes. Also, a stronger relationship would have been expected between years of study and scores in listening comprehension, as the early years should boost young learners’ receptive skills.” (p. 99)

8.

Le Temps, 23.6.2014. Interview mit Georges Lüdi, «Vater» des Sprachenkonzepts.

9.

“Pearson correlational analyses were performed in order to see if there was any direct relationship between the age that students began studying English and their scores on the three tests… The results of the analyses indicate that there is no significant correlation between starting age and the proficiency measures”. (p. 122)

“… these results seem to confirm the hypothesis proposed in Munoz (2006), according to which in the long term and after similar amounts of instruction or exposure to the tar- get language, no differences will be found due to starting age of learning”. (p. 128)

“… more attention should be paid to the needs that learners have to receive adequate amounts of quality input. Trusting young age of learning with the burden of learning success is clearly not enough”. (p. 130)

10.

11.

“It may be more efficient to begin second or foreign language teaching later. When learners receive only a few hours of instruction per week, learners who start later … often catch up with those who began earlier. Some second or foreign language programmes that begin with very young learners but offer only minimal contact with the language do not lead to much progress.” (p. 74)

“Research shows that a good foundation in the child’s first language, including the development of literacy, is a sound base to build on… It can be more efficient to begin second language teaching later.” (p. 186)

12.

Munoz, C. (2007). Symmetries and Asymmetries of Age Effects in Naturalistic and Instructed L2 Learning, Applied Linguistics, p. 1-19.

“… no evidence exists that an early start in foreign language learning leads to higher proficiency levels after the same amount of instructional time, and even younger starters with more instructional time have often failed to show a particularly substantial advantage in terms of long-term proficiency benefits”. (p. 9)

13.

- Kalberer compared early and late starters a) after the same instructional time but different ages and b) at the same age but with different instructional time.

The results showed the following:

- a) late starters outperformed early starters after the same instructional time in all areas of the ability test. With the same instructional time, older students learn more and learn faster.

- b) Despite the large difference in instructional time, the late starters are able to catch up very quickly. After only eight months, the late starters have already overtaken the students with one year of primary English. Equally remarkable is that the late starters reached essentially the same level as the students with two or four years of primary English.

“The results … indicate that older learners learn more quickly than younger learners and confirm the findings of a study by the same author (Cenoz: 2002). She compared 60 students aged 13 and 16 respectively after 6 years of English and the same amount of hours of English. The tests were designed in the following competencies: oral production, listening comprehension, grammar, cloze, composition. Given the same amount of hours and years LS (late starters) outperformed ES (early starters) in all aspects except pronunciation.

“Research into the optimal starting time should also include considerations about the distribution of instruction over the total school years. There are indications that more frequent periods towards the end of compulsory schooling are more valuable than a scarce early provision”. (p. 61)

14.

“… the research reviewed here on age, acquisition, and accent has, unfortunately, been appropriated by many educators and policy stakeholders to fuel the folk belief in the “earlier, the better” approach to foreign language education. Driven by this myth, private and public schools in nations around the globe have been introducing English to younger and younger pupils in the vain conviction that their children will emerge as extremely competent users of the world’s lingua franca… It is most unfortunate that the mammoth educational changes that have been effected to introduce English at lower and earlier levels of education by ministries of education and other supposedly responsible institutions have been based on misrepresentations of SLA research and on unsubstantiated intuitions.” (p. 43/44)

“… a clear superiority of late starters (older learners) in literacy-related skills (syntax, morphology, vocabulary, reading comprehension) is evident at Time 1, Time 2 and Time 3“. (p. 87)

15.

Munoz, C. (Ed.) (2006). Age and the Rate of Foreign Language Learning, Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Munoz berichtet über die Resultate des «Barcelona Age Factor Projects»: [6]

In sum

- late starters outperform younger starters after a similar quantity of hours of instruction;

- different rates of acquisition: younger learners slower, with “speeded progression between the ages of 11 and 13, much faster than that between ages 14 and 16″ (2006:31);

- adolescent and adult beginners rapid initial rate of learning after 200 hours;

- 11-year-old beginners made most progress between 200 and 416 hours and 8-year-old beginners made most rapid learning between 416 and 726 hours with both showing an increased learning rate at age 12, which may be due to an increase in cognitive development.

“Findings suggest that second language learning success in a foreign language context may be as much a function of exposure as of age. Exposure needs to be intense and to provide an adequate model” (2006:34).

In school contexts where opportunities for implicit learning and practice are minimal, older learners may be quicker to acquire another language.

“Older children show a faster learning rate, confirming the rate advantage of older children in the initial learning stages in an instructed situation as well.” (p. 9)

“The comparison between the different age groups after the same number of instruction hours … shows that the older-starting learners obtain higher scores at the three comparison times… All other contrasts indicate a significant advantage in favour of the older starters.” (p. 27)

“… there exists an age-related difference in rate of learning a foreign language in a school setting… older learners of foreign languages progress faster than younger learners.” (p. 28)

“L1 proficiency, associated with children’s cognitive development, was the factor with the strongest weight on the English scores of all the tests …” (p. 32)

“In a typical school syllabus, very little time is devoted to the foreign language (usually no more than three one-hour periods), and target language input is very limited (and part of it is usually accented). As a consequence, exposure is very scarce and probably insufficient for children to be able to make use of implicit learning mechanisms, and hence younger learners may not have enough time and exposure to benefit from the alleged advantages of implicit learning.” (p. 33)

“In all cases, 8-year-old starters with 200 and 416 hours of instruction in English obtained significantly lower correct discrimination scores than the other starting age groups”. (p. 48)

“Despite an advantage of six years in EFL for ES (early starters) LS (late starters) outperformed them towards the end of high-school education. This fact led the authors to conclude that an early start does not necessarily mean a lasting benefit.” (p. 91)

“… these findings are consistent with previous research in other formal contexts (Burstall et al. (1974); Oller and Nagato (1974); Singleton (1999), which do not provide evidence in favour of the ES either.” (p. 99)

“No current study, however, with the foreign language classroom as learning context has shown that young children catch up with adults and older children in the long run.” (p. 129)

“After the same number of instructional hours, children whose initial exposure occurred at an average of 8 years attain a lower average stage than those whose average age of initial exposure is at 11.” (p. 150)

“The implication for foreign language policy planning is that advancing the age of first exposure to the foreign language does not by itself guarantee a higher level of attainment at the end of compulsory schooling.” (p. 153)

“… an earlier start in a foreign language context does not mean reaching a higher level of ultimate attainment or a faster and more effective acquisition in the different subskills which form an integral part of the skill of writing.” (p. 177)

“The conclusion that can be drawn from this analysis is that “early” does not mean “better” in written development…” (p. 179)

16.

Singleton, D., and Ryan, L. (2004). Language acquisition: the age factor (2nd Ed.), Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

“The currently available empirical evidence on the age factor in L2 acquisition is not particularly helpful to those who advocate early L2 instruction.” (p. 227)

17.

“The authors conclude that, as expected, early age does not prove to be an advantage in the medium term and in a formal instructional setting as far as various indicators of phonetic development are concerned”. (p. x).

“As was found in the other chapters, the results show that the older learners have an advantage at both analysis times for communicative oral and aural interactive tests whereas for listening comprehension there were no significant differences.” (p. xi)

“Research has shown that in the limited setting of a formal classroom early L2 instruction does not prove advantageous.”

18.

Cenoz, J. (2002). Age differences in foreign language learning. In: International Review of Applied Linguistics 135-136: p. 125-142.

“The results indicate that the younger group obtained lower results in different dimension of language proficiency than the older group. In fact, the younger group obtained significantly lower scores in most of the analyses … These results indicate that students who started learning English in grade 6 (10-11 years old) present a higher degree of proficiency in English than students who have been exposed to the same number of hours of instruction but started learning English in grade 3 (7-8 years old)”. (p. 136)

19.

Lightbown, P. M. (2000). Classroom second language acquisition research and second language teaching. Applied Linguistics 21 (4), p. 431-482.

“… if the total amount of time of instruction is limited, it is likely to be more effective to begin instruction when learners have reached an age at which they can make use of a variety of learning strategies, including their L1 literacy skills, to make the most of that time” (p. 449)

20.

Marinova-Todd, S. H., et al. (2000). Three misconceptions about age and L2 learning. TESOL Quarterly 34/1: p. 9-34

“… introducing foreign languages to very young learners cannot be justified on grounds of biological readiness”. (p. 10)

“Children who study a foreign language for only a year or two in elementary school show no long-term effects; they need several years of continued instruction to achieve even modest proficiency”. (p. 28)

“Older immersion learners have had as much success as younger learners in shorter time periods”. (p. 29)

21.

Oller, J. W., and Nagato, N. (1974). The Long-Term Effect of FLES: An Experiment, The Modern Language Journal, Vol. 58, No. 1/2, p. 15-19

“The FLES (foreign language study in the elementary school) program did not have a lasting positive effect as measured by our tests”. (p. 18)

Quellen

[1] Strategie der EDK und Arbeitsplan für die gesamtschweizerische Koordination, 25. März 2004

[2] http://doi.org/10.22599/jesla.50

[3] https://folia.unifr.ch/unifr/documents/307816

Dass sich Politik und Medien weigern, unter dem Gewicht neuer Fakten und Erkenntnisse auf frühere Beschlüsse zurückzukommen, gilt auch für andere zentrale Zukunftsthemen, etwa die Energie- und Klimapolitik. Fast überall bestimmt in den meinungsmächtigen Institutionen eine Minderheit von privilegierten Akademikern ohne ideologische Diversity.

Das Sprachenkonzept der EDK ist seit seiner Einführung in arger Schieflage. Wie Urs Kalberer aufgrund seriöser Untersuchungen nachweist, gelingt es in der Primarschule nur einer Minderheit der Schülerinnen und Schülern, erfolgreich drei Sprachen nebeneinander zu lernen. Das ist ein bedenkliches Resultat, aber keinesfalls überraschend. Bedenklich sind nicht nur die Resultate im Frühfranzösisch, auch die Basiskenntnisse vieler Schüler im Deutsch sind als Folge der Zersplitterung des Bildungsauftrags völlig ungenügend.

Der Verdrängungseffekt der frühen zweiten Fremdsprache hat zu einem Abbau der sprachbildenden Realienfächer geführt. Statt in Geschichte und Geografie den allgemein bildenden Wortschatz im Deutsch zu fördern, wird Zeit vergeudet, um auf bescheidenstem Niveau das Gleiche in einer Fremdsprache zu probieren.

Das gescheiterte Experiment des frühen dreifachen Sprachenerwerbs kommt uns in jeder Hinsicht teuer zu stehen. Für viele Schüler, die durch das verfehlte Sprachenkonzept zutiefst verunsichert wurden, müssen umfassende Stütz- und Fördermassnahmen eingeleitet werden. Heilpädagoginnen können ein Lied davon singen, wie sehr sprachlich überforderte Kinder die Freude am Lernen verloren haben. An den Pädagogischen Hochschulen muss sehr viel Zeit investiert werden, um die Lehrpersonen für die wenigen wöchentlichen Fremdsprachenlektionen so auszubilden, dass die nötigen Kompetenzen zum Unterrichten vorhanden sind. Der hohe Aufwand für Aus- und Weiterbildung in den Fremdsprachen geht auf Kosten einer umfassenden Allgemeinbildung. Diese ist für die Gestaltung spannender und gehaltvoller Geschichts-, Geografie- und Naturkundelektionen von zentraler Bedeutung. Es geht letztlich um die Frage, wo der Schwerpunkt bei der Vermittlung kultureller Bildungsinhalte liegen soll: Bei den frühen Fremdsprachen oder den Realienfächern.

Wie lange will sich Die EDK den Misserfolg des forcierten Dreisprachenkonzepts noch leisten? Fremdsprachen primär aus politischen oder aus Prestige behafteten Gründen zu lernen ist pädagogisch verantwortungslos. Die Bildungspolitik muss sich endlich der schulischen Realität zuwenden und die Konsequenzen aus dem Sprachendebakel ziehen. Die Volksschule darf nicht länger ein Experimentierfeld für didaktischen Grössenwahn und politische Interessen sein.

Grün und woke – dann kommt es gut…

What are the main arguments underlying the strategy of teaching two foreign languages from primary school level according to the EDK-Sprachenstrategie 2004, and how do recent research findings respond to these arguments?

The main argument is ‘earlier is better’ as well as schoolchildren can easily learn multiple languages, which, of course is a confusion of two totally different learning environments: drip-feed learning at school versus massive exposition in a second language environment. In my post you will find extensive research-based findings. Why do you write anonymously?